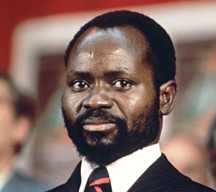

machel

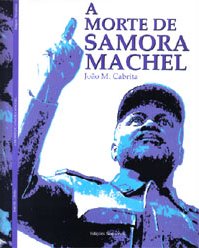

Unlike the assassination of Verwoerd, the death of Samora Machel wasn’t a JFK moment for me. I remember the shock of it but not where I was and what I was doing at the time. The first post-colonial leader of the country of my birth had died and it was suspected that South Africa, my adopted country, was responsible for the aeroplane crash that killed him along with 24 other passengers.

Unlike the assassination of Verwoerd, the death of Samora Machel wasn’t a JFK moment for me. I remember the shock of it but not where I was and what I was doing at the time. The first post-colonial leader of the country of my birth had died and it was suspected that South Africa, my adopted country, was responsible for the aeroplane crash that killed him along with 24 other passengers.It was twenty years ago today.

|

|

|

|

|

‘1985 stands out as a dark year in our history. The South West Africa (Namibia) issue was far from being resolved. South African troops were fighting in Angola. The high hopes raised by the 1984 Nkomati Accord between Mozambique and South Africa had dissipated.‘

We entered 1986 knowing that we’d be leaving the country (we left in February 1987), unlike previous years where we’d just talked about it. Apart from the effect that had on our minds, there is so much else that I remember from that year including two ‘JFK moments’ of mine, the disintegration of Challenger and the disaster at Chernobyl. It was also the year that Imelda Marcos became synonymous with an obsession with shoes. And it was the year of two political deaths rumoured to have been at the hands of the South Africans, Olof Palme and Samora Machel.

At that stage, Machel had been in power in Mozambique since independence from Portugal in June 1975. In his first few years of power, his revolutionary, Marxist zeal contributed towards massive strides in education and primary health care. These improvements were, however, accompanied by the abolition of all private property, suppression of free speech and huge relocations of the population, often to ‘re-education camps’ (quite a number of my friends from Maxixe were sent to re-education camps far in the north of the country because they smoked dope). Not that any of this affected his populist appeal which seemed to increase in proportion to the ever-increasing loathing from the white-minority regimes next door. Once the country descended into civil war with Renamo, an enemy first backed by Rhodesia, then by South Africa, the progress of earlier years was rapidly reversed.

Even in 1976, my last year at school, and still an enthusiastic communist, I felt very uncomfortable with some of the things that were being done in Mozambique in the name of ‘freedom and progress’. They were the things that South African racists loved to have as ammunition in arguments against democracy in South Africa. A joke with serious intent about the motives of the Soviets and its allies was doing the rounds at the time: Samora’s name stood for (SA)frica, (MO)zambique, (R)hodesia, (A)ngola.

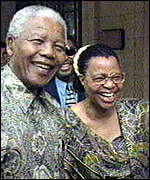

By the time of his death, the civil war in Mozambique had rendered most of the country ungovernable so the changes that came afterwards may have happened when they did had he remained alive although his successor, Joaquim Chissano, was a much more urbane, sophisticated man with much less of the stubborn, battle-hardened, freedom-fighter that characterised Machel. But, one thing that would probably not have happened if he were still alive today, is the romance between his widow, Graça Machel, and Nelson Mandela. Graça Machel is the only woman to have been the ‘first lady’ of two different countries.

By the time of his death, the civil war in Mozambique had rendered most of the country ungovernable so the changes that came afterwards may have happened when they did had he remained alive although his successor, Joaquim Chissano, was a much more urbane, sophisticated man with much less of the stubborn, battle-hardened, freedom-fighter that characterised Machel. But, one thing that would probably not have happened if he were still alive today, is the romance between his widow, Graça Machel, and Nelson Mandela. Graça Machel is the only woman to have been the ‘first lady’ of two different countries.A solemn ceremony will be held today on an isolated hillside outside Mbuzini, a South African hamlet, near South Africa's borders with Mozambique and Swaziland, the site of the plane crash that killed Samora Machel. South African President Thabo Mbeki and Mozambiquan President Armando Guebuza will be there. Graça Machel and Machel's children are expected to attend.

Whatever your opinions of Samora Machel, opinions that are bound to be clouded by your political beliefs, Mozambiquans still refer to him as 'o Pai da Nação', the father of the nation.

Update: BBC report on fresh probe into the cause of Machel's death.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home